Love in the Shadows of Power: How Valentine’s Day Is Quietly Reshaping Afghanistan

In a country long defined by war, political upheaval, and rigid social controls, an unexpected symbol is quietly making space for itself Valentine’s Day.

Not through loud parades or public celebrations, but through fashion shows, roses ordered online, discreet restaurant dinners, and whispered expressions of affection.

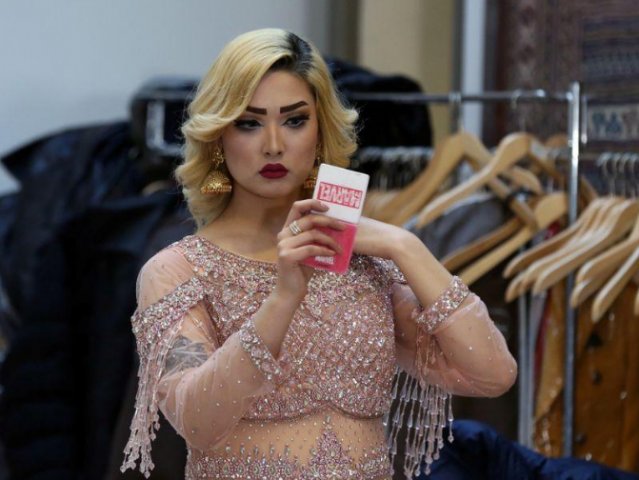

Earlier this February, a 20-year-old woman from Bamiyan province stepped onto a runway wearing a pink-and-yellow top paired with white jeans adorned with silver cuffs. As she completed her final walk and received her sash at a locally organized fashion competition, she delivered a statement that echoed far beyond the room:

“Valentine’s Day is known all over the world, and now it has found its place in Afghanistan too.”

The event also crowned a 23-year-old male model from Helmand as “Mr Valentine,” signaling something deeper than a fashion contest. In a conservative society shaped by decades of conflict, this moment represented a subtle but powerful cultural shift a generation choosing emotion over endurance, love over loss.

A Youth-Driven Cultural Undercurrent

Across Afghanistan’s major cities, particularly Kabul and Mazar-i-Sharif, February now brings discreet but visible signs of Valentine’s Day. Red and pink balloons appear in shop windows. Restaurants quietly advertise special packages for couples, complete with music and comedy performances carefully curated to remain low-profile.

For many young Afghans, Valentine’s Day is not about Western imitation. It is about psychological survival.

As one young woman explained, life in Afghanistan is already saturated with anxiety and fear. For her and many others, this single day offers a rare opportunity to express emotions that are otherwise suppressed.

Digital Love in a Conservative Society

With public displays still sensitive, online commerce has become the backbone of Valentine’s Day celebrations.

Murtaza Haidari, manager of the online store Kaaj, reported a sharp rise in orders for roses and teddy bears, mostly from young customers who prefer discretion over visibility.

“It is better to talk about love and emotions than fighting and war,” he noted.

One quote circulating among youth captures this sentiment with biting irony:

“The Taliban would not have gone to the front line if they had a lover at home.”

This statement, while informal, reflects a broader truth emotional deprivation fuels extremism, while emotional connection humanizes society.

Love as Quiet Resistance?

In Mazar-i-Sharif, a 23-year-old man planned a Valentine’s Day surprise for his fiancée, Nazanin. While unwilling to share details publicly, he confirmed one thing a bouquet of red roses.

Nazanin’s words perhaps best capture the mood of Afghanistan’s youth:

“Life here is full of tension. This is a small chance to enjoy feelings that remind us we are alive.”

These moments raise a critical question for international observers:

A Strategic Shift or a Silent Rejection?

Is the growing visibility of Valentine’s Day in Afghanistan a grassroots cultural resistance by young people—or could it also be a calculated signal by the Afghan authorities seeking international recognition?

There are two competing interpretations:

1. Youth-Led Cultural Defiance

Young Afghans, disconnected from ideology and exhausted by conflict, may be carving out emotional autonomy. Valentine’s Day becomes a non-political protest, expressing values incompatible with authoritarian control, choice, affection, individuality.

2. Soft Image Management

Alternatively, could selective tolerance of such events be a tactical move? Allowing controlled cultural openness may serve as a message to the international community: Afghanistan is changing; engagement is possible.

The reality may lie somewhere in between..

Global Relevance: Why the World Should Pay Attention

For audiences in Europe, North America, and Canada, this story resonates because it reframes Afghanistan not through geopolitics alone, but through human aspiration.

It challenges stereotypes.

It complicates narratives.

And it highlights a generation that does not fit neatly into headlines.

Love, in this context, becomes political not by intent, but by consequence.

Valentine’s Day alone will not transform Afghanistan.

But its quiet spread tells us something important: people do not want to live in permanent fear.

Whether this movement grows or is curtailed will reveal much about the future relationship between Afghan society and those who govern it.

The world should not ignore these small signs. History often turns not on grand declarations but on whispers of change.

If love can survive in Afghanistan, even briefly and quietly, then the question is not whether Afghan society wants change but how long it can be denied.

Source: The Express Tribune